Chữ Nôm and Hồ Xuân Hương: Unraveling the Complexity of the Former Vietnamese Written Language and t

- Rachel Egoian

- Mar 11, 2018

- 6 min read

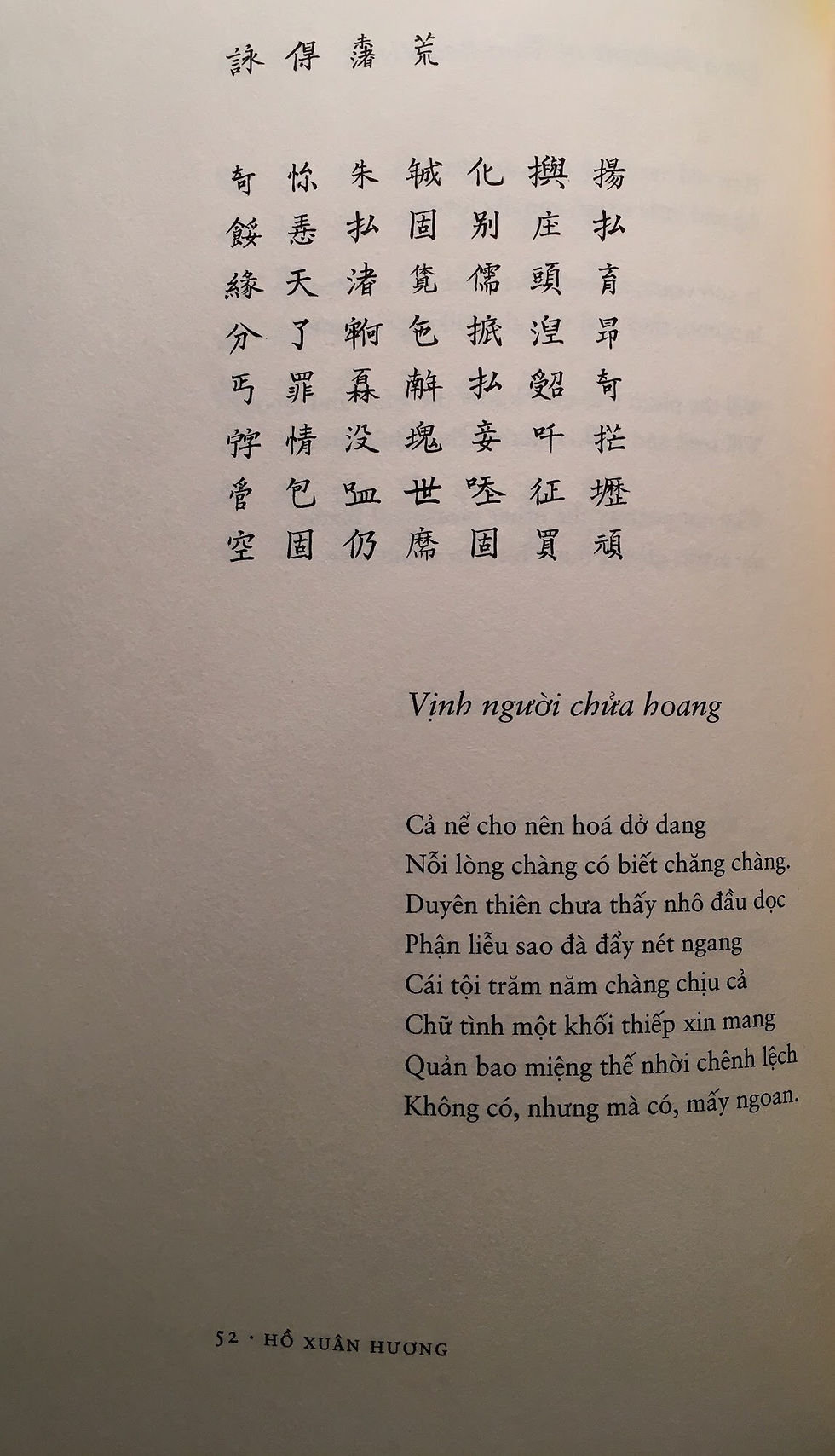

When we think of language and its written form, it goes through many changes and processes over time due to societal pressures of colonialism and imperialism. Language works as a marker to transcend its origin point and becomes a symbolic meaning to change with purpose to further explore hidden aspects of culture and identity. Coincidently, I was fortunate enough to stumble upon a story about an artist’s revival of the extinct Filipino writing calligraphy known as Baybayin. Through the representation of art, the artist uses the ancient calligraphy to incorporate graffiti as a progressive lens that educates the public about culture and identity. The idea of transforming older forms of writing through different modes of expression allows for visibility among minority groups that resurfaces the history and culture as physical references to our ancestors’ pasts. Therefore, the mysteries of Hồ Xuân Hương’s life and her poetry are examined and translated in the book called Spring Essence: The Poetry of Hồ Xuân Hương by John Balaban, in which he aims to unravel the complexity of the Vietnamese ancient writing, chữ Nôm, or Nôm calligraphy.

Balaban notes that there is little information about Hồ's life. She was born between 1775 and 1780 in the Lê Dynasty during its societal collapse in which the Vietnamese traditional literature began to take shape with the themes of individual longing and a sense of permanence. She originally came from the Hồ family in the Quỳnh Đôi village, Quỳnh Lưu District, Nghệ province in north Central Vietnam. While growing up, she was taught classical literature; however, her father’s early death lead to the misfortune to her education, thus risking her chances of marriage as well.

Nôm calligraphy transforms Hồ's writing style to push even further the male traditional style through the influence of the common people and sexual innuendos. In addition, it breaks away from the literary tradition as well as providing access for the common people to read her poetry. Back then, literature was mostly viewed and studied by the upper-middle class. So, Nôm calligraphy helps maintain a progressive masculine voice directing its attention to the common people as its audience. It is mainly directed towards a political stance or propaganda due to societal corruption where Hồ creates an awareness for the common people and women to fully understand society's pressures of corruption in its main focus on women status and male authority.

In John Balaban’s introduction, he shares the background of Hồ Xuân Hương and where her poetry derives from. As an unconventional poet during the eighteenth century of Vietnam, Hồ writes in the male, Confucian traditional style, suggesting that even though women at that time could hold authoritative roles in armies and economic management, women unlikely had the opportunity for higher education, especially in literature. However, Hồ’s revolutionary influences focuses on the concepts of women status and male authority as underlying effects of female oppression challenging the themes of love and fate as a progressive stance against the patriarchal structure. Nôm calligraphy empowers her poetry to express a new voice in the Vietnamese traditional poetic style that conveys the experiences of the common people, which allows the reader to explore Hồ Xuân Hương’s construction of imagery working to expose her vulnerability and gain authority over her gender role. With the rise in controversy in breaking away from the literary tradition, Hồ’s writing in the lu-shih sonnet-like style along with its sexual innuendos encourages her rebellious attitude to emphasize her ability to deconstruct society’s corrupted patriarchal structure.

Analyzing Hồ’s poem, “On Sharing a Husband”, reconstructs the traditional Vietnamese poetic style through transforming the themes of love and fate as part of the deeply rooted issues to women status and male authority. With vivid imagery, the poem addresses:

Screw the fate that makes you share a man.

One cuddles under cotton blankets; the other’s cold.

Every now and then, well, maybe or maybe not.

Once or twice a month, oh, it’s like nothing.

You try to stick to it like a fly on rice

but the rice is rotten. You slave like the maid,

but without pay. If I had known how it would go

I think I would have lived alone (Balaban, 35)

From Balaban’s notes, the reference to the Vietnamese translation, “chém cha (‘screw’) is a curse, meaning ‘cut father,’” represents an attack on male authority regarding the gender inequalities within marriage. As far as fate’s involvement with the speaker’s frustration, the poem expresses the anxieties of female oppression through confining women to the domestic role. With the reference of slaving like a maid, tensions rise against the female gender role by focusing on the issues with domesticity in forcing women into servitude. The speaker has a lack of interest regarding her self-worth from the comparisons of the fly and rotten rice, which suggests imagery of decay and loss, exposing the speaker’s vulnerability and lack of authority over her gender role. On the other hand, with the poem’s sonnet-like structure, the volta or turn shifts the speaker’s emphasis on isolation by insisting that she would have lived alone had she known that she would have to share a husband, which challenges the idea of gaining back independence and authority over the self as well as defying expectations of the role of women, stepping outside of the female gender role. The concepts of love and fate are contributing to female oppression because the speaker insists that the faults with marriage have to deal with fate and love’s inability to work together. During this time period, Vietnamese literature was about “cruel fate” and “fated love” drawing connections to marriage’s influence to determine the outcome of an individual’s legacy and lineage.

In the realm of women, religion guides as society’s influence on order regarding the strict rules and behavior. Hồ’s poem, “Buddhist Nun,” provides a perspective about women in religion impart to the debt of love where religion meets its controversy of properly understanding the world without the true ideals of love and fate. During the eighteenth century in Vietnam, nunneries became an exploration for women in breaking away from their duties of marriage and committing to religion in the hopes of Enlightenment Falling to religion, relinquishes to the injustices on the female gender role because it limits the woman’s independence in seeking out new perspectives of the world that brings true enlightenment of love and fate. Religion disguises the practices of peace and love by sheltering and impeding a woman’s sense of well being (self), questioning where does a woman’s independence and duty follow. The poem suggests:

Many pink-cheeked girls abandon the world.

Many vain spouses break their marriage vows.

But women go forth, leaning on the Bodhisattva’s staff,

clutching Buddha’s rosary, telling the beads,

hoping to raise sails to shores of Enlightenment,

afraid of huge waves that might shatter halyards.

Whoever is lucky enough to become a nun

must hold on dearly in order to succeed (Balaban, 83).

Hồ unravels the fate of women with two options: marriage or religion. In doing so, the speaker challenges religion, specifically Buddhism when referencing the Bodhisattva’s staff as a symbol of spiritual awakening to question the speaker’s intentions of the passage’s satirical tone. Is the passage mocking the “Bodhisattva’s staff” in which women are not actually experiencing a spiritual awakening due to being confined to their gender role and enforcing their love and fate to be cut off from the world?

As we contemplate Hồ Xuân Hương’s influence to history and to our world, she was not afraid to take risks in order to support equality for women dealing with societal pressures. She challenges us to think independently when it comes to understanding political, economic, and religious endeavors. It is important to explore the language, culture, and history of our people and look closely at the challenges they have faced. As people of color, how do we make sure to include our culture and identity as part of society’s influence in a positive stance for equality?

If you like stories like this, subscribe to Chopsticks Alley.

Rachel Egoian - Pleasant Hill, CA

Contributor

Originally from the Bay Area and a recent graduate from University of California, Santa Cruz in Literature and Education, Rachel has a profound interest in Asian American literature and communities. Coming from a mixed ethnic background as an Armenian, Irish and Filipina, she values the importance of culture and self-identity. Through the foundations of literary criticism, she encourages and stresses the need for diversity in literature.